Fresh bid to tackle illegal wildlife trade

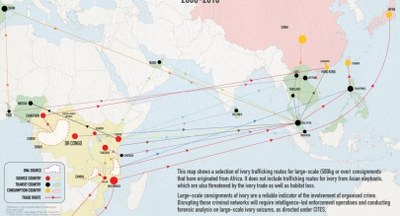

With nations in this region being both transit and destination points, officials are looking at ways to reduce the demand for wild animal products on the ground and to improve political and judicial measures to prosecute traffickers.

According to USAID Wildlife Asia, which jointly organised the 4th Regional Dialogue on Combating Trafficking of Wild Fauna and Flora along with several other conservation agencies in Bangkok last week, it is clear that wildlife trafficking is a sophisticated enterprise organised by crime syndicates.

As such, it needs to be tackled through innovations in law enforcement and better government policy.

Sal Amato, the agency’s law enforcement specialist with more than three decades of experience, said the traffickers were often one step ahead of the officials.

“There is one overriding principle that drives the business -– it’s of huge value with low risk. And that’s why we are losing the battle, rapidly.”

According to the agency, four key species are its focus in this region. Elephant ivory, rhino horns, tiger parts and pangolin products are among the top items in the illegal wildlife trade worldwide. And the trade in these products is particularly rampant in Southeast Asia and China, which are both major sources of demand and transit points.

On average, the worldwide trade is worth around $20 billion (Bt662 billion) annually, with several cases being underreported. Because it involves criminal syndicates, the activity is viewed as undermining the rule of law and encouraging corruption and money laundering. It is therefore cited as a critical security issue.

Dr Robert Mather, chief of party at USAID Wildlife Asia, and other wildlife specialists at the event pointed to the unabated trend of wildlife trafficking, especially from Africa to this region.

First to arrive here were parts of two prime African species – rhinos and elephants.

Jeremy Swanson, a law enforcement specialist from USAID in Tanzania, said the population of African elephants had been declining rapidly due to poaching since 2009 or so, with Tanzania seeing more than 60 per cent of its population lost exclusively for ivory. The killings reached a peak in 2012 or 2013, and the rate has dropped slightly, partly due to more stringent law enforcement, he said.

His statistics are in line with those from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which shows that more than 41 tonnes of ivory was seized in 2013, the highest so far this decade. Of an estimated 500,000 animals in the wild in 2012, around 20,000 were poached, and the IUCN noted that the poaching and trade in ivory could wipe out up to one-fifth of the population within 10 years if it is allowed to continue.

The sadder story is of the region’s black rhinos. About 96 per cent of the population dropped during the years 1970-1992, with the number dipping to as low as 2,400. The good news is that the population has now risen to around 4,800, partly due to renewed stringent protection measures and relocation programmes, the agency noted.

Mather, who has been working on wildlife conservation in this region for decades, has observed the latest trend of trafficking of wild animals from Africa to this region involves pangolins. He said pangolins are among the most-traded species worldwide. As many as 1.1 million were found being trafficked between 2006 and 2015 globally.

However, fewer than 10 per cent of the smugglers ended up being prosecuted and sentenced, prompting Mather to point to flaws in the processes that need to be fixed.

According to studies by his agency, the demand is a result of growing consumption of these species’ parts for purposes ranging from medications to expensive trophies.

Mather said consumption-reduction activities needed to shift from just awareness-raising to encouraging behaviour change among those who consume in wildlife. Law enforcement and policy changes are equally critical, he said.

Mather said there is a relatively low number of prosecutions and sentencing of wrongdoers in wildlife trafficking cases in this region, and concerned parties have to do more to make law enforcement more effective.

“We see a lot of arrests but these hardly ever lead to successful prosecutions. We really need to move forward to the sentencing,” pointed Mather.

Amato said factors preventing more prosecutions included inadequate financial and human resources, lack of adequate laws, inadequate equipment and training, low awareness among the judiciary, lack of political will and, last but not least, corruption.

“It’s a question whether it’s inept or corrupt,” he said.

In an attempt to address the issue, wildlife specialists agreed on more cooperation and timely information sharing via new technology, as well as work at the judicial and political levels. Thailand, the experts said, is progressing with work at the Supreme Court on the judicial processes, while the Asean Interparliamentary Assembly has started to look at the issue of enforcement against trafficking.

“The big question remains: why these cases often disappear, and do not continue to the end in sentencing,” Mather said.

(This is first published in The Nation, by Piyaporn Wongruang, a Thai journalist who attended the Media Workshop on Combating Wildlife Trafficking in ASEAN and China, organized by USAID Wildlife Asia)